Heartstopper, Florida’s ‘Don’t Say Gay’ Legislation, and the Importance of Imagining Better Futures

A couple recent events have made me think about where LGBTQ issues stand in the United States: the release of the Netflix show Heartstopper, the leak of the draft majority opinion in Dobbs. v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, and the broader milieu of LGBTQ rights legislation currently passing through state legislatures and various judiciaries. Intellectually, I find that the issues raised by these events are nicely illustrative of a few core themes and tensions that arise in our examination of living good lives. However, these issues are also more than just intellectual curiosities for me — they resonate quite existentially — and I hope to leave you with some sense of that existentialism by the time you finish reading. A sense of why these issues matter not just practically but also ethically and morally. Why you, perhaps, should be very bothered by the current situation in the United States. So, today will end up being a deeply personal exploration of what we do to queer youth and what we should learn from it.

Before we examine this story, it’ll be helpful to signpost a few ideas that will frame and explain parts of the narrative. When I applied to nationally competitive scholarships in my final two years at Virginia Tech, I premised my applications around a few central tenets, including:

That the social context in which healthcare is delivered has an equal to or greater than impact on health outcomes than the biology itself, depending on the outcome and/or disease of interest

That the convergence of incredible computational and data resources allows us to understand and address the social and biological elements of health with greater nuance than ever before

That physicians must (a) treat the social context of health outcomes as seriously as the biological context and (b) have advanced computational skills so that we can fully leverage the opportunity presented by tenet #2

Now, tenet #3 is an easily misunderstood proposition. The sheer amount of biology that physicians are expected to learn during medical school and residency is immense, and tenet #3 tacitly adds the expectation that physicians learn a great amount of information about social determinants of health and explicitly adds the expectation that at least some physicians learn a great amount of information about mathematics, statistics, computer science, data science, and more. A common pushback to tenet #3 goes something like: “When are we going to learn all of this? There’s no time!” I’ve gotten a version of this comment from beloved Reviewer #2, and it's an understandable concern.

In response, I might raise tenet #1 or underscore that many medical trainees already receive training on social determinants of health but that there is broad variability in the quantity and quality of said education depending on the training program. However, I’d also acknowledge that physicians have different specialties. The exigence of tenet #3 is less that individual physicians need to be experts in social determinants of health and more that physicians as a body politic need effective ways to address the social context in which healthcare is delivered. This actually makes tenet #3 an even trickier proposition, for it removes physicians from a context in which they are treating “purely” medical issues and places them in a context in which they are addressing both medical and political issues.

But physicians already do this! They treat patients every single day whose symptoms are a result of biological and social processes. It's the child with asthma who lives in an area with significant air pollution, or the person with a once-manageable chronic illness that is now life threatening because of a lack of access to health insurance. This is where the ideas of ‘treating the whole patient’ and biopsychosocial medicine come from. While giving these patients medications to treat their acute issues is undoubtedly helpful and necessary, helping them to live in a less polluted area or to find access to health insurance will do far more in the long term, and I believe that physicians (as a body politic) should have as vested an interest in helping a patient find housing or health insurance as they do in prescribing a medication. Put differently: if the greatest causes of disease are environmental and not biological, then the ethos of physicians-as-healers should compel us to address those causes, even if they aren’t “purely” medical. With this in mind, let’s turn to the inciting incident of this story.

So there I was…

Two weekends ago, I spent Saturday evening doing something rather uncharacteristic: I binged the entire season of Netflix’s newly released show, Heartstopper. Heartstopper is an adaptation of a series of graphic novels by Alice Oseman that focuses on the burgeoning teenage romance between its main characters Charlie Spring and Nick Nelson.

It. Was. Everything.

It was the most wholesome piece of content I’ve seen in a long time — I laughed, I cried, I smiled — and it filled my heart with an utter sense of joy. There were several moments in watching Heartstopper where I recognized what felt like the setup for standard conceits in gay stories that, refreshingly, never ended up being true. For instance, the conceit where one character in the soon-to-be gay relationship kisses a member of the opposite sex when the other member of the soon-to-be gay relationship is observing from afar. This results in the relationship completely breaking apart before it’s rebuilt over the course of several painful chapters or episodes. I’m particularly over this conceit — I just want the characters to be happy! — and I was immensely pleased when Heartstopper just discarded with all this faff in the episode where Charlie and Nick attended Harry’s party.

But almost immediately after finishing all eight episodes of Heartstopper, I started to feel a sense of deep melancholy. I wished that I’d had this show when growing up, and I wished that I’d had the experiences this show portrayed when growing up. While not a universal experience, I’ve spoken to many gay guys who feel like growing up gay took something from them. Everyone you know is busy having first dates and first kisses, asking people out to Homecoming or Prom, and saying ‘I love you’ to their first, second, third, fourth, and fifth girlfriends and boyfriends. You know, typical teenage stuff.

And while this is going on, it feels like the world is passing you by as you struggle to accept who you are or to find others like you, and all this forces you to grow up faster than other people, to find other outlets through which you can survive or numb the pain. For some, this means turning towards risky behaviors like taking drugs or having unprotected sex. For others, it means incessantly striving towards traditional metrics of success like good grades and well-respected jobs.

In 1973, Andrew Tobias put forward the “Best Little Boy in the World” hypothesis in a book by the same name. The “Best Little Boy in the World” hypothesis posits that gay boys deflect attention from their sexuality by pursuing other markers of success, and in a recent paper, Joel Mittelman, an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Notre Dame, provides empirical evidence in support of this hypothesis. Mittelman’s paper is an excellent example of how the rich computational and data resources mentioned in tenet #2 allow us to understand the social elements of health with greater nuance than before — in the case of Mittelman’s paper, education.

The worst kept secret in education is that women drastically outperform men. This is known as the gender gap, and it’s something that academics and policymakers alike have puzzled over for some time. In an analysis of newly available federal survey data that included information on the respondents’ sexual orientations, Mittelman adds to our understanding of the gender gap by demonstrating that there is a strong interaction between gender and sexuality when it comes to educational outcomes. Specifically, gay men are more likely to outperform straight men, straight women, and lesbian/bisexual women on multiple metrics of academic performance while bisexual/lesbian women are more likely to underperform on these metrics. Interestingly, this pattern for gay men holds across all racial/ethnic groups and birth cohorts, and the effect is so strong it leads to a little fact I love: if gay men in the United States formed their own country, they would be the most highly educated country in the world.

Mittelman proposes that the distance gay boys feel from heterosexual norms frees them from toxic stereotypes such as the idea that doing well in school is ‘womanly,’ and it pushes them to excel academically as a way of responding to status threats like being called or considered a fag. If you’re a young gay boy, you may not be able to have your first kiss or ask someone you want out to Homecoming, but you can study. You may not know whether your family and peers will accept you, but you can study. And that’s all that really matters: people care much less about other aspects of you if you’re an academic all-star. You’re the smart kid instead of the gay kid. As Mittelman expounds, academia offers an easily masterable set of rules (i.e., get good grades) to gay boys who otherwise struggle to master the complex rules of heterosexuality and who want so deeply to deflect attention away from who they are.

All of this begs the question: why do we have a culture that pushes young gay boys into doing this? While there are many contributors, I would identify our media environment that both reflects and molds broader cultural values as a significant factor because it influences the possibilities of what we believe our lives can be. And let me just say, LGBTQ media offerings have left a lot to be desired. In fact, let’s do a quick review of some of the biggest hits from queer cinema in the past two decades (major spoilers ahead):

Brokeback Mountain (2005) —> An iconic story of two ranchers who repress their true selves and have a tortured love affair over several decades until one of them dies. The other lives with the pain of having never lived truly. A heart wrenching tale.

Milk (2008) —> Fantastic film that never ceases to make me cry. Details the historic life of Harvey Milk, the first openly gay politician in the United States. Milk is assassinated at the end of the film.

Prayers for Bobby (2009) —> Featuring the iconic Sigourney Weaver as Mary Griffith. Follows the lead-up to and aftermath of gay teen Bobby Griffith’s suicide due to his mother’s intolerance. Mary eventually realizes there was nothing wrong with her son and becomes a staunch LGBTQ rights activist. Also heart wrenching…

Carol (2015) —> A tale of two 1950s lesbian lovers whose sexuality is used to bully, harass, and blackmail them. The ending sees the two women united, but not before they’ve lost many things. Complicated.

Moonlight (2016) —> A poignant exploration of the intersections between blackness, masculinity, and queerness. Chiron learns over time that he must hide his sexuality to survive, but in the end, he finds the beginnings of acceptance. Complicated.

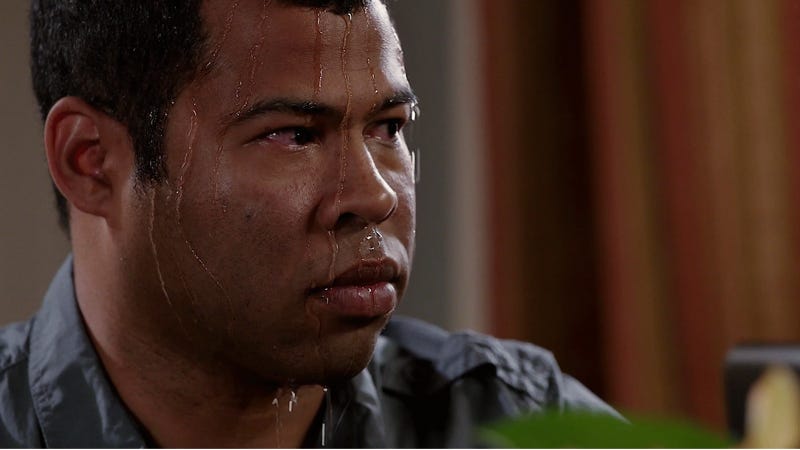

Call Me By Your Name (2017) —> I absolutely love this film. But the ending is literally three minutes of Timothée Chalamet crying in front of a fireplace. Let’s call it… emotionally complicated!

120 BPM (2017) —> A story of AIDS activists living in Paris in the 1990s. Need I say more? One review called this a “skillfully woven and at times unbearably sad portrait of activists…”.

Love, Simon (2018) —> Okay, this one is actually happy and pure. Win #1

Do we sense a theme here? These are poignant films that deal with emotionally intense topics, and in all but Love, Simon, the main characters suffer in some way because of their sexuality. Think about what message that sends to queer youth.

I cannot remember a single book I read as a young teenager that featured an openly gay character let alone a positive plot line about their sexuality. The one movie I watched featuring a gay character was Prayers for Bobby, which — as detailed above — deals with some pretty heavy themes. Media representation for me growing up was watching the national debate over same-sex marriage play out on the evening news.

10/10 would not recommend.

YouTube was a particular solace for me. On YouTube, you could find videos of actual gay people talking about their lives and emphasizing an incredibly important message: it gets better. That simple message provided hope that a better day would come, and the importance of that cannot be understated. Yet, that message also reflected and shaped a reality in which happiness for queer youth was something delayed. When I grew up, there was nothing showing me that my life could be good right now, and that is why I would have given anything to have had a show like Heartstopper. It pushes the radical message that happiness for queer youth is not something to be deferred until some unbeknownst time in the future; it’s something they can have right now. And we are getting so much more representation like this! Paul Stamets and Hugh Culber in Star Trek: Discovery, Netflix’s Queer Eye and Sex Education, and books! So many amazing books featuring young queer characters who are happy and just living their lives.

While it’s difficult to quantify the effect that this type of representation has on LGBTQ youth, there is some data we can look at to formulate our ideas. A 2011 mixed methods study of a small number of LGB individuals reported that media role models played an important role in the process of self-realization and coming out for the participants as well as in fostering senses of pride, inspiration, and comfort. Meanwhile, a recent Gallup poll reported that 20.8% of Gen Z respondents identified as LGBTQ — the largest percentage for any generation we have data on. I’d posit that the positive shift in the media environment played an important role in this trend, and my frustration is that at the exact moment that we’re witnessing this incredible change in the media landscape for LGBTQ youth, we are also seeing a sordid backlash.

States like Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, and Tennessee have passed laws that either ban or criminalize gender-affirming care for trans youth, while states like Texas and Florida have released public guidance deterring the practice. Several of these laws are now making their way through the courts, but parents of trans children in these states are terrified, even making plans to uproot their entire lives so that they can continue to provide their children with the affirming care they need. Florida also recently passed its so-called ‘Don’t Say Gay’ legislation, which earned its nickname from the following passage:

Classroom instruction by school personnel or third parties on sexual orientation or gender identity may not occur in kindergarten through grade 3 or in a manner that is not age appropriate or developmentally appropriate for students in accordance with state standards.

Now, this text is quite innocuous on the face of it (hint: it’s designed that way), but like many regulations it makes use of broad verbiage that is entirely meaningless without considering the wider political context in which that verbiage is enacted. What is considered “age appropriate” and “developmentally appropriate” is largely going to be dictated by the values of those in power, and individuals targeted by the legislation (i.e., teachers, principals, and school board members) are likely to act in a precautionary manner to avoid the scrutiny of those more powerful than them, particularly when that legislation opens them to civil liability as is the case in Florida. Couple this raft of legislation with the fact that so many LGBTQ books are banned from schools and that the punditocracy is currently discussing how likely it is that same-sex marriage will be overturned in light of the leaked draft Dobbs v. Jackson opinion, and you have a national environment that is decidedly unfriendly towards LGBTQ youth.

According to a recent survey done by The Trevor Project, 45% of LGBTQ youth in the United States considered suicide in the past year. Forty. Five. Percent. What are we doing here? This is not the result of some innate biological difference between LGBTQ youth and non-LGBTQ youth, and while I’m not going to claim that this is entirely due to the actions of politicians who are actively targeting children, I’m going to go out on a limb and say that they’re really not helping. We are messing with the lives of these children, and it is disgusting.

So where does that leave us? Unfortunately, there are no easy answers. If you care about health outcomes as I do, this is fundamentally a political problem — not a biological one. This is why I believe physicians need to be just as concerned about the social context of care as they are about the biological context. This is why I believe physicians need effective ways as a body politic to address social issues. Our ethos as healers compels us. And that leaves us with the long, hard work of doing politics — something that is messy and exhausting and not guaranteed to deliver the changes that we want or need.

Now, that may be an emotionally complicated end to this post, and that’s in some ways unavoidable given the topic. But I will say this: if you’re the parent of a tween or teenager and you’re reading, please sit down with your kid(s) and watch Heartstopper or give them some books that have queer characters. You don’t need to make a big deal out of it or have a conversation. Just do it! One of the biggest protective factors for LGBTQ youth in terms of their mental health is having accepting family and friends, and if you’re blessed to have a queer kid and you just don’t know it yet, you’ll be showing them that you are accepting and that a better world is possible now. And that’s worth everything…

Coming Up…

Hopefully you enjoyed today’s blog. I have several things coming down the pipeline, including:

Book Review: “Mental Training for Climbers” by Arno Ilgner

Case Study: Organ Transplantation Policies in the United States and the Importance of Stating Your Assumptions in Modelling

Reflections on My Two Years Studying in the UK on the Marshall Scholarship

The Past, Present, and Future of Funding Scientific Research

Why Genomics Has Paid Big Dividends in Medicine While Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning Have Yet To Deliver

If something above piques your interest, let me know in the comments below, and I’ll push it to the top of the queue. If you want me to cover something else, let me know that too! ‘Til then!